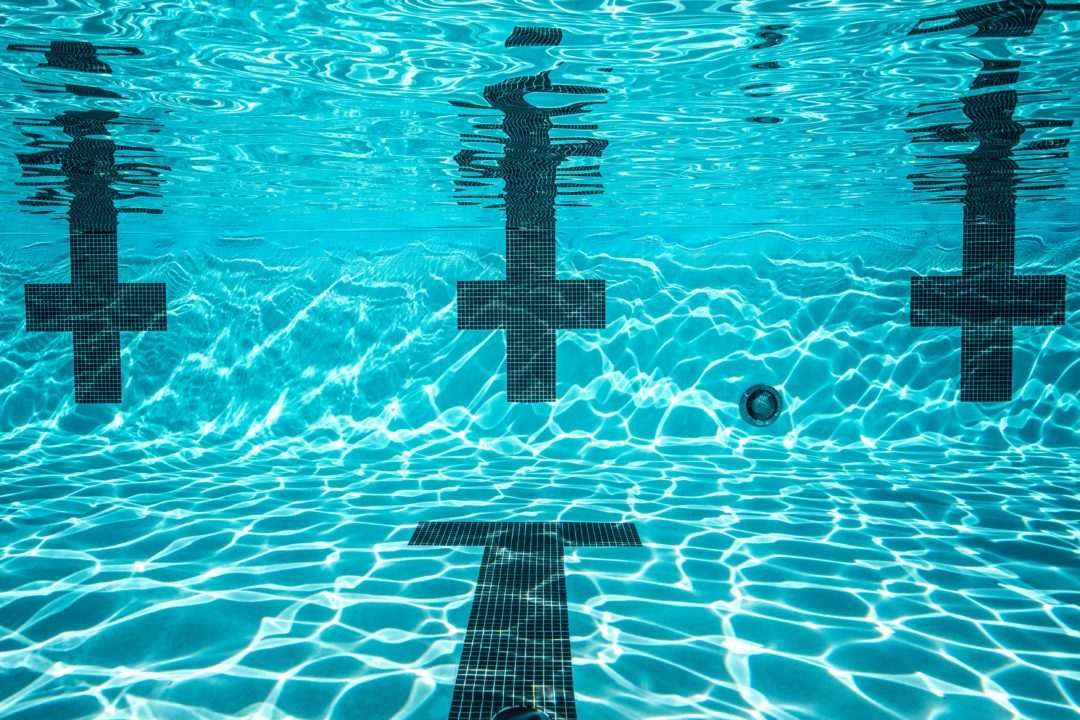

Courtesy: John Holden

You do not have to be an expert psychologist to realize that we are more likely to repeat a pleasant experience than an unpleasant one. Unfortunately for some, a swimming experience has been upsetting, while for others, there can be some form of reluctance towards a journey into the unknown, subsequently leading to a fear of drowning irrespective of any previous experience. However, the majority of children and adults adapt and enjoy swimming because the whole journey into the unknown has no doubt been made a pleasant one. There are a variety of reasons as to why which I will endeavor to explore and expand on so as teachers you will have a basis for a practical progression.

The starting point is the elimination of fear and reluctance, but it will take patience, understanding and differentiation. This tolerance is governed fundamentally with the hard fact that man as an animal does not naturally belong in the water. There is evidence that babies can submerge and float just under the water but they cannot stay there for any long periods as man is not amphibious. However, as man is formed in the womb, in a liquid, and the evolution process suggesting that man originated from the sea, can man naturally adapt to being in water? Evidence confirms that he can to an extent; although not in an amphibious way. Synchronized swimmers with the way they perform their routines provides a perfect example of man adapting to water. This opens a significant talking point. Is learning to swim “natured” or “nurtured?” To simplify, do they swim naturally after adequate water time or does the skill have to be learned? The answer is that the skill has to be learned in an adequate amount of water time so that man can adapt.

Swimming teachers can present evidence of situations where students are reluctant to get started but by the end of the first or second lesson, they are performing a front paddle. On the other hand there are students who appear comfortable and happy to enter the water after a number of lessons but still lack both the skill and confidence to gain the impetus to swim. In order to get to the root of this problem we have to look closely at the way they perceive depth.

In the early sixties, two psychologists Gibson & Walk made an apparatus called a visual cliff with a shallow side and a safe deep side. Approximately thirty-two babies aged between six and fourteen months were called across both sides by their mothers. None of the babies ventured over the “deep” side although there was no problem over the shallow side. However, the experiment is not conclusive in that only thirty-two babies took part, from only one culture and there was no data as to an age when children were able to cross the deep side using the visual cliff.

Meanwhile, If we take the experiment at face value we can conclude that it is the student who is in complete charge of the learning and not the teacher. The babies would not venture over the deep side on the visual cliff, meaning that a student will swim or acquire a skill when they are ready for it not when we think they aught to be. With the adaption of empathy and sympathy to enable us to tolerate this, we are able to move forward into the practicalities of our pool side practice.

It can be an achievement for some merely to get into the water but once in the water, this depth perception does not instantly disappear at any age and is constantly on the mind of the student hence the fear of sinking and subsequently drowning. This is why all beginner classes should take place in water shallow enough for beginners to stand comfortably no deeper than a water level between the waist and just under shoulder level. When we then progress and introduce our skills it can break a huge psychological barrier for the beginner knowing that they can now put their feet down on the bottom and taking on Whiting advice, Never put the learner in a position which (s)he is likely to fail (Whiting 1970)

This involves feet off and on the bottom practices in the initial stages to reassure all pupils that they are learning in their comfort zone. An initial progression idea is for them simply to take steps, in different directions to feel for that secure reassurance that they can feel the bottom. That achieved then small progressive stages must be introduced to over come a common reluctance to put the face in the water and the ones who dare always invariably hold their noses. Therefore, try getting them to draw shapes and names in the water with their noses. Now, do it with you hands behind you back! Let’s try a submarine. One hand behind your back the other up, fist clenched. This is the periscope, bend your knees head completely under, – down you go. stand up immediately. I now want you to do five bobs; head under completely on every bob, fold your arms, now get in pairs and let your partner count your bobs. A further progressions can include a “limbo” Two pupils hold a woggle horizontal on the surface. The class make a line and they have to duck under the woggle without touching it . They go to the back of the line, two different students hold the woggle and so on. Any reluctance, simply go round and join the line again. For improves moving to deeper water after say 10 meters, their ability to put their feet on the bottom at any time is paramount. Therefore, walking a width, swimming half a width, feet down and walking the rest of the width are excellent starting points. To vary it you could get them hopping across walking backwards and so on.

There are two general theories which try and overcome fears their phobias “Systematic Desensitization” or “Flooding.” The older generation’s experience may recall the latter when the “teacher” sat you on the pool side, came along and with a little nudge, you were in! You then had to meet the fear “head on” There is evidence that it works and is quicker than the former because the more you meet the fear head on it gradually diminishes but for most this approach is both undesirable and dangerous.

I sincerely hope that all teaching programs are now based upon a type of Systematic Desensitization approach where the pupil adapts to the skill in small, bite size, manageable pieces so that (s)he can gradually move closer towards the fear, adapt and totally eliminate it. All very well in theory, but how does the teacher make this happen in practice?

Like all learning situations the rate of learning with individuals varies considerably. One of the most common definitions of learning is that Learning is a relatively permanent change in behavior as a result of an experience. (Hardy & Heyes1984) Terms such as “off the mark” or it “has clicked” are all common phrases used by teachers when the pupil achieves their initial few strokes or acquires a new skill. The result in this case has not been a change of behavior as defined but the acquisition of skill as a result of an experience. In order to achieve this the theme of play is used

The more opportunities a child is offered during the course of play, the more likely it is that new learning will take place” (Fontana D 1995) Alman adds that Creative play is like a spring that bubbles up from within a child. (2019)

However, play has to be used correctly which means it has to be creative. If used effectively the student be it child or adult – as I will explain further in a case study – will not realize that the learning is having an affective and learning will be a secondary stimulus. Fontana’s premise of play is based on the practicalities of Classical Conditioning where the reinforcement is presented before the conditional stimulus. I will exemplify this in a case study.

I met an elderly swimmer in Canada called Marie who had learned to swim at 84 years old. There had been a huge phobia since Marie nearly drowned in a river as a teenager. What got her to swim was the introduction of a new stimulus to replace the uncontrolled stimulus being her inability to swim. Her daughter got her involved in an aqua fit program. Just prior to this her daughter and her friends came round after they had been to aqua fit and started talking about how enjoyable it was and that Maria realized she was missing out, so off she went to the aqua fit. This different, relaxation was incompatible with fear and therefore, Marie gradually learned to swim. stemming from the other aquatic stimuli. Although Maria was 84 it was the theme of play which provided the controlled response – her ability to swim. The “play” in Maria’s case was the aqua fit.

What was also taken into consideration in this case study was to adapt some form of relaxation therapy. It is based on the early work of Wolpe and Eysenck H (1958) It is designed to replace the phobic stimuli with a new response that is incompatible with fear. Maria undoubtedly learned in a “comfort zone” in the initial learning process which she clearly enjoyed as a basis but if students are constantly in this zone learning will be static. In order to achieve the desired outcome with complete beginners, teachers have to get them out of their comfort zone so that the synapses in the brain fuse together to create the inertia. How do we achieve this? By applying “Systematic Desensitization” as outlined which will be more effective when it is supplemented with both Classical Conditioning (CC)which I have discussed and Operant Conditioning (OC) all of which run parallel with taching activities. OC is the opposite to CC as the reward comes after the desired outcome opposed to CC where the reward comes before.

How do we use “reward” in OC? There are the obvious palpable rewards: badges, stickers and certificates are examples but more significantly, the rewarding of serious intent. For each action performed by the beginner or indeed the improver, there is a consequence. It may result in an undesired out come and although wrong in the teacher’s eyes a genuine attempt at the skills has been made. A skillful teacher will some how twist the undesired out come round into a desired outcome. Practicing educators possess an unlimited reservoir of good ideas (Anon) However, praise and thanks giving are further ideas for reinforcement, but should only be used when a desired outcome has been achieved. Too many rewards can have a negative affect such as the constant use of saying “good” and “well done” after every attempt.

Meanwhile, you can use as many re-enforcements as you want in a lesson but they can become quickly extinct if the teacher cannot apply them correctly to the purpose of objectivity. The greatest reward and reinforcer is to leave the student overjoyed so that (s)he is so excited when it is time for them to attend their next lesson.

(c) John Holden 2019

References

Almon J Salesian Calendar Don Bosco Publications 2019

Fontana D Psychology For Teachers 1995 Macmillan Press

Hardy M Heyes S Beginning Psychology 1984 Weindenfield & Nicholson

Whiting H T A Teaching The Persistent Non-Swimmer 1970 Bell & Sons London

About John Holden

John Holden has a degree in Education (BEd) and is a qualified high school teacher and swim coach in the UK. He has been coaching and teaching for 38 years. Holden was the UK’s keynote speaker at the International Federation of Swimming Teachers (IFSTA) conference in Hong Kong in 2004.