Courtesy: Malavika Vishwanath

Note: This is an article originally published on July 17th, 2021 on the universality selection process. There have been some recent updates to the Olympic Qualification criteria for the Paris 2024 Olympics, as well as the terminology reflected in the original article.

The recent changes are briefly outlined below, followed by the original article.

1) Swimming federations were informed by World Aquatics earlier this month (April 2024) that the requirement for Universality nominees to have competed in the 2023 or 2024 editions of the World Aquatics Championships, has been removed. Instead, World Aquatics stated that federations are “obligated to enter the male athlete and the female athlete who have achieved the highest World Aquatics Points Table score in any individual Olympic event, as achieved at a World Aquatics-approved qualification event during the qualification period, using the World Aquatics Points Table, 1st January 2024 edition“.

The selection priority order remains the same as previous Olympic cycles. This change is identical to the removal of the requirement to participate at the 2019 Gwangju World Championships in order to qualify for a Universality spot at the Tokyo 2021 Olympics. However, this update comes much later in the Olympic cycle as compared to Tokyo. The most recent update to the qualification criteria can be read here.

2) The qualification criteria published by World Aquatics on January 25th, 2023, which states the requirement to participate in the 2023 Fukuoka World Aquatics Championships and/or the 2024 Doha World Aquatics Championships in order to earn a Universality nomination, can be found here. This document updates the terminology used in previous Olympics to reflect the “Olympic Selection Time/OST”. Now, the OST has been renamed the “Olympic Consideration Time/OCT”.

3) As of December 2022, FINA has been rebranded as World Aquatics; any references to FINA in this article can be considered equivalent to World Aquatics.

ORIGINAL ARTICLE – JULY 2021

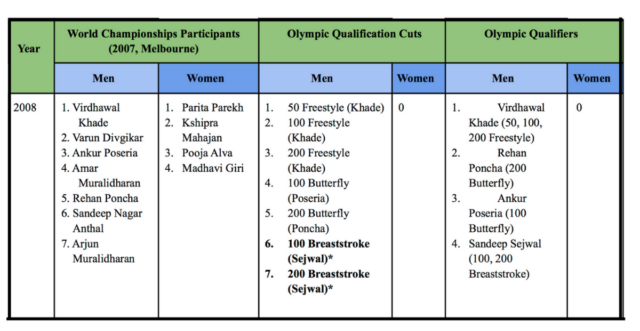

Over the past month, Sajan Prakash and Srihari Nataraj rewrote the history of Indian swimming by becoming the first two Indian swimmers to achieve automatic qualification standards for the Olympics. Their accomplishments mark the peak of men’s swimming performances in India, which have been improving consistently over the past decade. Starting with the historic four-man roster sent to the 2008 Beijing Olympics, Indian men have been delivering international-caliber performances, and have consistently achieved multiple qualification standards every Olympic cycle.

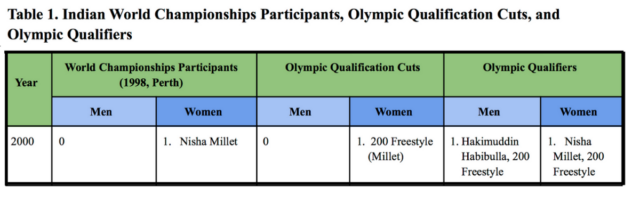

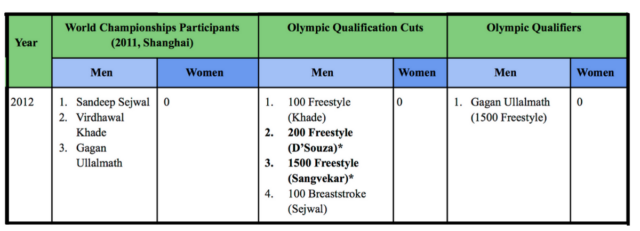

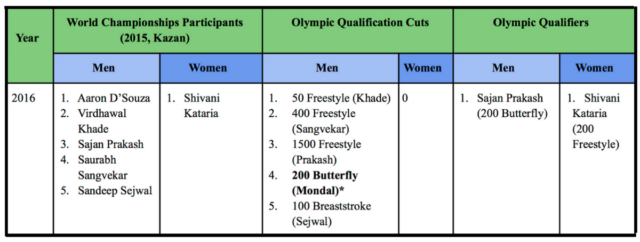

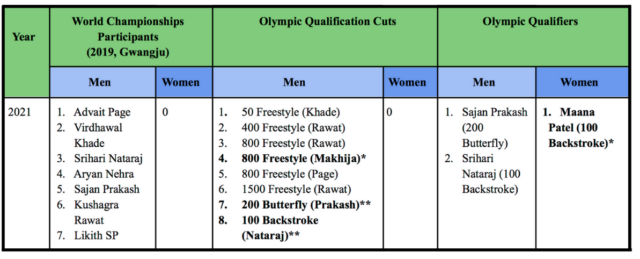

However, while talking about the international successes of Indian swimming, it is also important to acknowledge its shortcomings. So far in the history of our sport, we have seen 21 male Olympic swimmers including Prakash and Nataraj, and only seven female Olympic swimmers including Maana Patel, who was most recently nominated under the Universality Quota to swim at the Tokyo Olympics. The Beijing Olympics marked the start of a period where our male swimmers began consistently outperforming our women at the international stage — they started sitting higher on world rankings, competing more frequently at high-level international meets, and winning more major international medals. Since 2008, Indian men have achieved twenty-six Olympic qualification cuts, while zero have been achieved by Indian women (see Table 1). Why is it that we have such a drastic gender gap between males and females with regard to international performance?

The Olympic Qualification Procedure

FINA, the international body that governs the sport of swimming, uses the Olympic Qualifying Time (OQT / ‘A’ cut) and the Olympic Selection Time (OST/’B’ cut) as time standards to qualify for the Olympics. The ‘A’ cut is significantly faster than the ‘B’ cut; countries whose swimmers have met the ‘A’ cut are eligible to send a maximum of two swimmers per event to the Olympics. For instance, if two swimmers from the USA achieve ‘A’ cuts in the 100 freestyle, they will both be allowed to represent the USA at the Olympics in the 100 freestyle. The ‘B’ cut is a slower time, and the significance of this cut has been altered through the years. Between 2000 and 2008, achieving a ‘B’ cut meant automatic Olympic eligibility, and countries whose swimmers had met the ‘B’ cut were eligible to send a maximum of one swimmer per event to the Olympics. For instance, if two swimmers from India achieved ‘B’ cuts in the 100 butterfly in 2004, only one of them would have been allowed to represent India at the Athens Olympics in the 100 butterfly.

In 2012, FINA introduced some rule changes that altered the prioritization given to swimmers with ‘A’ and ‘B’ cuts. Swimmers with ‘A’ cuts still remained automatically eligible to qualify for an Olympic team and were placed highest on the priority list, followed by swimmers on relay teams. The term “Universality Places’’ was officially introduced, and was a provision that enabled Olympic participation among countries whose swimmers have no qualification cuts. Participation in the edition of the World Championships that took place the year prior to the Olympics became the mandatory criterion for Universality eligibility. Universality nominees were prioritized higher than swimmers with ‘B’ cuts; an athlete who ranks among the top five swimmers with ‘B’ cut in an event could now be knocked out of the Olympics by a Universality nominee who has not met the cut in any event. The order of prioritization (‘A’ cuts, Relay swimmers, Universality nominees and ‘B’ cuts) remains in effect to this day. Therefore, the ‘B’ cut, a standard that once ensured Olympic participation is now very unlikely to earn a swimmer an Olympic spot.

Indian Swimmers at Major International Meets

The first two Indian swimmers to achieve Olympic ‘B’ cuts were both women — Nisha Millet achieved the mark in the 200 freestyle and competed in the 2000 Sydney Olympics, and Shikha Tandon achieved ‘B’ cuts in the 50 and 100 freestyle and competed in the 2004 Athens Olympics. No woman since Tandon has achieved an Olympic qualification cut, while 24 ‘B’ cuts and two ‘A’ cuts have since been achieved by Indian men. Interestingly, most of the performances that earned our men their ‘A’ or ‘B’ cuts after 2008 occurred at the international level, and almost none occurred at the national level. Note here that national-level meets in India are rarely ever approved by FINA, meaning that any Olympic qualification cut that is achieved at a domestic meet in India cannot be officially ratified. Consequently, FINA-approved international meets are the primary avenue through which an Indian swimmer can achieve a ratified qualification cut.

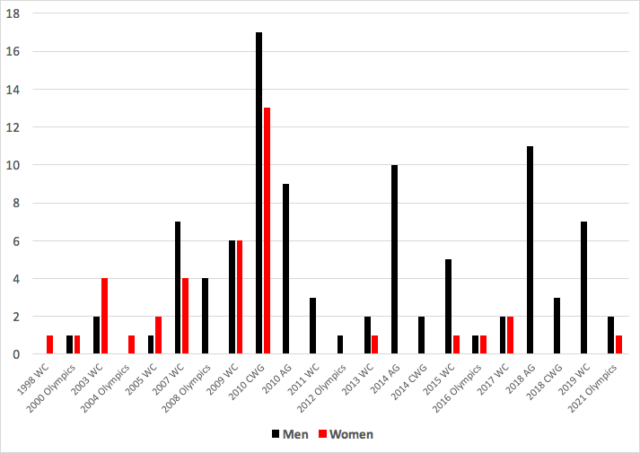

The graph below shows the number of male and female Indian swimmers sent to major international meets between 2000 and 2021. (I’ve treated the 2010 Commonwealth Games as an outlier, since India was the host country and we saw more participants at this meet than at any other major international meet). Between 2000 and 2009, the ratio of male to female participants was approximately 1:1. However, after the 2009 World Championships, 8 out of 14 major meets saw zero female participation, and an additional four meets saw only one female participant. Between 2010 and 2021, the ratio of male to female participants was almost 10:1. The greater number of men being sent to major international meets created more opportunities for them to achieve ratified Olympic qualification cuts, a factor that could have contributed to the large gender gap in the number of qualification cuts in India.

Figure 1. Gender Differences in the Number of Indian Male and Female Swimmers sent to Major International Competitions (2000–2021). WC = World Championships, CWG = Commonwealth Games, AG = Asian Games.

The Universality Quota and Gender Differences in Performance

(Note: Most of this section draws on the information presented in Table 1)

The difference in the number of qualification cuts between males and females, combined with the introduction of the Universality quota, has had vastly different effects on the performances of men and women; the men having multiple qualification cuts led them to strive towards eliminating the need for the quota so that they can all participate, while the lack of qualification cuts amongst women has led them to perpetuate the need for its existence to ensure that at least one woman can participate.

However, the Universality rules dis-incentivize the need to achieve an Olympic qualification cut when no one is close to achieving it. In India, where our female swimmers have no qualification cuts, participation at a mandatory World Championships is solely invitation-based. In a normal non-pandemic year, when a female swimmer is not nominated to participate in a World Championship meet, her door to the Olympics automatically closes. On the contrary, when a female swimmer is nominated for a World Championships spot, her Olympic qualification is set in stone and no one can take her place.

Therefore, the incentive for someone who didn’t participate in a World Championship meet to swim faster and achieve a ‘B’ cut in the year-long period between a World Championships and the Olympics becomes drastically lowered, since another swimmer’s Olympic spot has already been rendered immutable. Since slower Universality nominees almost always override swimmers with faster ‘B’ cuts, where is the motivation to swim faster to try and achieve a ‘B’ cut in the first place?

Let’s illustrate this with some examples. In 2015, Shivani Kataria was the only female Indian swimmer to have been sent to the Kazan World Championships, making her the only female to be eligible for a Universality nomination. Consequently, her spot on the Rio Olympic team was guaranteed. Even if another female swimmer (let’s call her Janani) achieved a ‘B’ cut at a FINA-approved Olympic qualification meet, Kataria’s automatic Universality nomination would put Janani out of contention for the Olympics despite only the latter having achieved a qualification cut. Even if Janani’s time ranked her in the top five among all swimmers with ‘B’ cuts, Kataria would still outrank her due to the high prioritization of Universality nominees.

This year, owing to the pandemic, the Universality clause no longer mandated participation at the previous year’s World Championships. The only requirement was participation at any FINA-approved Olympic qualification meet over the course of the qualification period between 1st March 2019 and 20th June 2021. More significantly, the deadline for this year’s Universality nomination fell a week before the deadline for achieving ‘A’ or ‘B’ qualification cuts. Sixteen women were eligible for this year’s Universality nomination, owing to their participation at the FINA-approved 10th Asian Age Group Championships held in India in September 2019. Three of these women, Annie Jain, Bhavya Sachdeva, and Chahat Arora, participated at the FINA-approved Thailand Swimming Championships in October 2020. In June 2021, two women, Maana Patel and Kenisha Gupta, competed in FINA-approved meets at Serbia and Rome. Apart from Gupta and Patel, no other swimmer among these 16 women competed at a ratified qualification meet in 2021.

Incidentally, the Belgrade Trophy in Serbia was both the first and the last meet in 2021 that could earn a female Indian swimmer a Universality nomination; the Sette Colli Trophy in Rome was held between 25th and 27th June, which was past the nomination deadline. Patel emerged from this meet ranking higher than Gupta, therefore rightfully securing her Universality nomination.

Here’s the issue: Even if Gupta ended up ranking higher than Patel in Rome, she would still have been ineligible for a Universality nomination. Furthermore, the improvements that any of the 11 other eligible swimmers may have made since the Asian Age Group Championships become irrelevant, since they had not not participated in a ratified qualification meet since September 2019. The same goes for the three swimmers who participated at the Thailand Swimming Championships in October 2020. Even earning a ‘B’ cut at a domestic meet in 2021 would not have improved their Olympic chances, since no Indian meets were ratified by FINA.

The nearly two-year period between the Asian Age Group Championships and the end of the Olympic qualification period could have seen 16 women competing amongst themselves for an Olympic spot. However, the competition ultimately came down to two women, and history repeated itself as the meet in Serbia replaced the World Championships as the singular competition that determined one’s Olympic fate.

Let us contrast this with what happened on the men’s side. In 2016, Sajan Prakash was one of three men with ‘B’ cuts who were eligible for a Universality nomination. All three men regularly participated in Olympic qualification meets that cycle, providing ample fuel and opportunity for competition amongst themselves. Prakash put himself in the best position for Olympic contention by achieving ‘B’ cuts in three different events, which was the highest number of ‘B’ cuts achieved among the three eligible men), therefore earning his Universality nomination. On June 20th of this year, Srihari Nataraj earned a Universality nomination that would be nullified owing to Prakash achieving the ‘A’ cut in the 200 butterfly in Rome on June 26th. In an incredible feat, Nataraj responded with an ‘A’ cut of his own through a time-trial in the 100 backstroke in Rome the next day. Both swimmers are now guaranteed spots on the Olympic team.

The contrast between the experiences of the men and the women was that, in both 2016 and 2021, multiple men were eligible and actively competing for a single Olympic spot; in order for these men to put themselves in the best position for Olympic contention, they each had to outperform every other man they were competing with.

This consequently improved men’s performances so much between 2016 and 2021 that the cycle of relying on the Universality quota was broken this year, and our Olympic berths were no longer limited to just one man.

On the other hand, one woman was guaranteed an Olympic spot in 2016, and only two women out of a possible 16 swam a single meet to compete for an Olympic spot in 2021. This did nothing to improve the performances of Indian women; no form of improvement could have increased another woman’s chances of earning an Olympic berth in 2016 since Kataria’s Universality nomination was immutable, and barely any of the Universality-eligible swimmers competed in a ratified meet in 2021, leading domestic improvements to fall on blind eyes where FINA is concerned. In short, the opportunity and drive for men to compete against each other was what pushed them to perform. Since the opportunity to compete was virtually nonexistent among the women, their performances showed little improvement.

Why not just aim for an ‘A’ cut?

All this being said, why don’t our women just aim for the automatic qualification standard? Achieving ‘A’ cuts in a developing nation like India is far easier said than done, as evidenced by the fact that this was the first time in Indian swimming history where ‘A’ cuts were achieved. Significant monetary investment goes into helping a swimmer improve their performances in order to achieve a qualification cut, making the sport extremely expensive if one does not have access to external funding.

The lack of FINA ratification at meets in India means paying out of your pocket to attend a ratified meet in another country; those who do not have the means to compete internationally rarely have the opportunity to achieve ratified qualification cuts. The lack of a tangible criterion such as a qualification cut among Indian women makes it so that funding is more easily accessible by men, who do have a well-established history of qualification cuts to show potential sponsors. Furthermore, there is a disconnect between sport and academics in India, making it so that you need to choose between your sport or your education at 18.

An Olympic hopeful with no external funding needs to shell out large sums of money while potentially sacrificing their education and future, in order to bank on an Olympic qualification procedure that provides no guarantees. Consequently, there is a huge attrition rate among female swimmers after the completion of age-group level competition. The constant need to recycle talent from the age-group level in order to combat the fall-out at the senior level severely hinders the country’s ability to sustain success in order to achieve a qualification cut. It is not the lack of talent that has led Indian women to falter at the international level; it is the systemic issues that hinder this talent from being nurtured for periods long enough for one to achieve an Olympic qualification cut.

The Downfalls of the Universality Quota: A Summary

By mandating participation at the World Championships, the Universality quota creates an all-or-nothing scenario where you are either nominated to participate in the World Championships, or sit out of the Olympics. Furthermore, prioritizing Universality nominees higher than swimmers with ‘B’ cuts makes the incentive to try and achieve those cuts incredibly low. As a result, earning a nomination to a pre-Olympic World Championships (following which one is virtually guaranteed a spot on the Olympic team despite potentially having slower times than their teammates who were left off the roster) becomes much more attractive than performing well enough to qualify for the Olympics. Even this year, when the World Championship participation requirement was taken away, the requirement that replaced it was participation in a FINA-approved Olympic qualification meet. Since none of these meets took place in India, any attempt to make a qualifying cut at the national level would have been futile since it could not earn one an Olympic berth. In short, by simultaneously guaranteeing Olympic participation while de-emphasizing the need for fast swimming, the Universality quota creates a cycle that is lethally detrimental to performance in a developing country such as India.

Olympic qualification cuts are ‘B’ cuts unless otherwise indicated.

*Indicates the swimmer did not participate at the corresponding event.

ABOUT Malavika Vishwanath

ABOUT Malavika Vishwanath

Malavika Vishwanath is originally from Bangalore, India, and swam competitively since she was seven years old. Over her 15 year-long career, she swam for India at the World Short Course Championships (Doha 2014 & Windsor 2016), and the World Junior Championships (Singapore 2015). She is a 2x Asian Age Group Bronze Medallist (Bangkok 2015), and a 4x South Asian Games Gold Medallist and Record Holder (Assam 2016). Malavika also holds the current Indian National Record for the 1500 Freestyle. She swam for Drew University from 2016-2020, where she earned DIII All-American honors in the 1650 Freestyle in 2018. A 2020 NCAA Woman of the Year nominee, Malavika is a 15-time Landmark Conference Champion and 3-time Individual CSCAA Scholar All-American. She obtained a BA in Psychology from Drew University, and an M.Ed in Counseling and Sport Psychology from Boston University. Malavika currently practices as a Counseling and Sport Psychologist with athletes across India.

Certainly a lot of information. Especially tough for coaches and swimmers to keep updated with the Universality qualifying procedures considering there have been changed each Olympic cycle.

Wonder if this causes a nation’s system to just aim for a Universality slot since achieving an OST (A cut) is tough.

Also it may need some analysis if it causes swimmers (girls) to drop out around 15-19 yrs when it becomes clear that they are aiming for just the one slot.

There is a natural conflict between the athlete and the governing institution that no amount of tinkering will eliminate.

The athlete finds success through hard work and discipline; the institution finds success in growing working capital. Neither cooperates with the other’s objectives.

It is the swimmer who gets the gold, and the swimmer that sets the time. Does this present a problem?

“Permission” or “invitation”; what business does the institution have in the athlete’s free exercise of gifts and talents?

It boggles the mind, the time and energy spent on manufacturing participation trophies, when there is only one way to beat an Olympic Champion.

For the love of the sport, give it back to the swimmer.

Thanks for this article. While I do think Universality is a useful category in a number of ways, I agree that it also has had a number of pitfalls. As the author suggests “locking” a person into the countries universality spot has not been helpful in building a base of people pushing for that spot. I think the requirement of having to go to Worlds is detrimental to developing depth in a nation. So I do think the dropping of that “worlds requirement” is a good thing. But the timing of that has not helped the current crop. As also noted, costs of getting to approved meets may also prove detrimental to fostering depth development as this will invariably be… Read more »

Great article! I’m curious about the barriers to ratified meets in India though.