Courtesy: DESTRO MACHINES, a SwimSwam partner.

I was in the airport coming back from Christmas vacation in 2018, and my friend and former teammate who swam with me at Purdue University texted me, ‘Missy Franklin just retired, shoulder problems’. Having been a competitive swimmer for most of my life, having watched Missy become an international swimming sensation, and now being a sports rehab chiropractor who takes a special interest in shoulder injuries, it hurt me to learn that a fellow swimmer had to end her swimming career early for a shoulder injury. So, instead of shrugging off the frustration and getting on with my life, I decided to turn it into action, and write this article for you, whomever “you” are. With the hope that it will help at least one person with a goal to “…just keep swimming.”

- Maybe you are a swimmer who has a really ugly MRI and you’re thinking about surgery.

- Maybe you already had surgery, and you’re thinking about another one.

- Maybe you are contemplating retirement because you don’t want a surgery and you simply can’t swim because your shoulder hurts. And I mean, really hurts.

- Maybe you’ve tried all the things, and the exercises, and the treatments and nothing is working because every time you get back in the pool to try again, you keep getting injured.

If this sounds like you, then I urge you to keep reading and don’t lose hope.

Case Study: One of the worst shoulder cases I’ve seen presented with multiple rotator cuff tears, labral tearing, bursitis, and osteoarthritis. As far as a shoulder goes, it doesn’t get much worse until you start looking at trauma cases. He’d had steroid injections, done some Physical Therapy, and was wanting to avoid any further procedures or going in for surgery if possible, especially as a middle-aged man who loved not only swimming, but surfing, and lifting weights. After several months of diligent work, he is happy to say that he’s pain-free in his day-to-day, and training without any major limitations. Although he does admit it ‘talks to him’ every now and then, he says he ‘knows what to do when it goes off track’.

That last statement is critical. Knowing what to do to get your shoulder back on track is one of the hardest, but most rewarding things to find out. If this ordinary patient of mine can help himself with a little of my guidance, what do you think that you can do?

What does a shoulder want?

Like any negotiation situation, you must first know what the other side wants.

- Movement: this is the part of swimming that keeps shoulders, for the most part, happy. Once shoulders stop moving, they start a feed-forward cycle that tricks you into thinking if you give it rest and immobilization that it will get better on its own.

- Balance: At the risk of over-simplification, shoulders shoulder have 180 degrees of rotation at 90 degrees abduction (arm out like an airplane), balanced muscular strength of the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. Swimmers typically have either a problem of hypermobility (too flexible) or they have a range of motion imbalance that causes injury.

- Blood Flow/Circulation: Every cell in the body needs flow of blood and fluid to repair tissues and decrease buildup of inflammation. This is like cash-flow in a budget and the more you spend the more you need to make, or you’ll overspend.

- Coordination: Shoulders are the most mobile joints in the body, and the stability of the shoulder largely depends on the brain and how it coordinates the muscles around the joint. This is the most important part of building shoulder resilience. Can you move your shoulder in a figure eight with ease? If you can’t control your body, you can’t expect to protect it from injury.

- Technique: This is about putting it all together and putting stress on the joint in a position of alignment rather than malalignment.

- Rest: Overtraining and overstraining are rampant in any sport, but particularly in swimming when it comes to shoulder injuries. Building yardage and strength training too quickly over time and putting too many yards over time on top of poor technique, poor joint function, or both lead to injury.

What does an injury prone shoulder look like?

James Magnussen of Australia, who retired amidst a left shoulder injury and subsequent failed surgery, was one of Australia’s fastest 100m Freestyle swimmers in history. Seen in several underwater videos, his left shoulder is a good example of poor scapular position during the catch phase of the stroke. Unfortunately, I’m not able to share any underwater footage from his races in this article because I don’t own the video footage, but if you are so inclined, you will see in his left shoulder what I am about to discuss.

There are other points we could review with his freestyle technique, but for the sake of time, we will focus our attention on the left shoulder. We do know that his left shoulder was injured and operated on in 2015 as we can see from his social media posts.

Here are some reasons how his left sided technique could have been responsible for the injury to his shoulder:

- Scapular protraction, elevation, and anterior tilting (Shoulder goes forward and elevated): there is nothing inherently wrong with moving your shoulder blade up and forward, but the shoulder should never be fully loaded in this position during the catch phase of the stroke, especially when the elbow is not in line with the scapula.

Here in this picture of poor technique, and I’ve drawn lines to indicate we don’t have alignment of the scapula and the humerus which causes the shoulder to sit forward in position. This is a particularly poor position when the swimmer is about to ramp up muscle tension and propel themselves forward. – courtesy DESTRO MACHINES

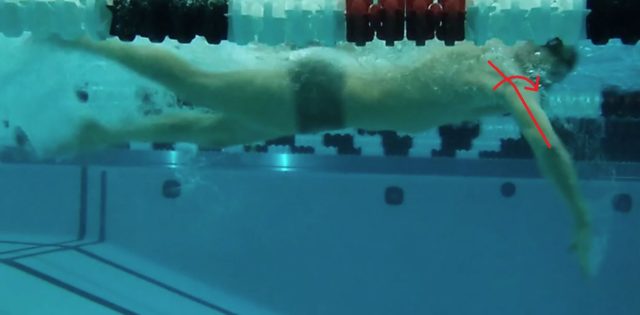

Here is another poor example from the lateral aspect. This one is complicated, because it appears this swimmer has good alignment of the scapula relative to the humerus, but due to the 2D image we are seeing, we can’t appreciate that in this case, the shoulder is elevated, protracted, and anteriorly rotated. – courtesy DESTRO MACHINES

- High Elbow Catch: This is a common technique because coaches are noticing high propulsion rates when you can get your forearm perpendicular to the floor. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it has to be done in a biomechanically safe way (see below). It becomes especially problematic when the swimmer’s shoulder happens to be deeper than the elbow.

Here is a good example of shoulder (centration) alignment during a high elbow catch phase. It has room for improvement, but as far as alignment from a lateral view, this is good. – courtesy DESTRO MACHINES

- Pathomechanics: Seen in James Magnussen’s stroke, the position of the shoulder is not centrated (in line) with the glenoid (shoulder socket), which puts strain on surrounding soft tissue structures. He has failed to maintain the alignment between his glenoid (shoulder blade), humerus (arm bone) during the catch phase of the stroke, causing his shoulder to self-destruct over time.

- Resulting Injuries: Here are some examples of injuries that can result from this type of swimming technique.

- Most commonly in swimmers, injuries can include labral tearing, rotator cuff tearing, tendinopathy, bursitis, or some combination of those injuries.

- The biceps (long head) tendon, which attaches to the labrum of the shoulder, with excessive and improper loading can cause labral injury (SLAP tear).

- Impingement of the subacromial space (shoulder impingement).

- Excessive and repetitive loading in this position causes shortening of the posterior shoulder capsule resulting in range of motion deficits (GIRD-glenohumeral internal rotation dysfunction)

The Fix:

- The Stroke: at this point in the stroke (the catch), you should be loading your shoulder and preparing to propel yourself forward and finish your stroke.

- This means you need to have your shoulder in a “packed” (down and back/’scaptioned’) position so that the humerus (arm bone) and the glenoid (shoulder socket) are in alignment. We call this ‘joint centration’.

- The Kick: which is always the hardest part for timing with the arms will assist in body positioning so that the scapula and humerus are in alignment during the catch phase of the stroke.

- Body Position: in order to align the shoulder, you should rotate your body so that the sternum, the glenoid (shoulder socket), and his humerus (arm bone) are in alignment during the catch.

- A good example of a swimmer who has more biomechanical resilience to injury will display better alignment, based on the relation of, the rib cage, the spine of the scapula (shoulder blade bone landmark), the humeral head (arm bone head) and the humeral shaft (mid portion of the humerus), during the catch phase.

- Doing this results in better coordination and length-tension relationship of the scapular stabilizers (shoulder blade muscles) with the posterior rotator cuff (shoulder joint stabilizers) and posterior shoulder muscles.

Summary

- Swimming with better technique and understanding more about how to rehab shoulder injuries can help keep you out of early retirement and improve your performance.

- Loading the shoulder, repetitively, in a ‘de-centrated’ position can (and eventually will) cause injury.

- The position and coordination of movement of the scapula (shoulder blade) is the most important part of maintaining good shoulder position.

- The position of the body and timing of the kick play an important role in achieving optimal shoulder position in the cycle of the stroke.

- Identifying and correcting this poor stroke technique early in a swimmer’s career is important, but it’s never too late to make your stroke safer and pain free.

- The Bad: The worst position for the shoulder seen in examples above, is when the scapula is elevated and protracted and tilted anteriorly, with the humerus misaligned from the glenoid during the catch phase of the stroke.

- The Good: The best and strongest position for the shoulder to be in, seen in examples above, is when the scapula is protracted, depressed, and externally rotated, while keeping alignment with the humerus during the catch phase of the stroke.

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to diagnose or treat an injury. If you have shoulder pain and are attempting to manage it on your own, stop and work with a professional who is licensed to diagnose and treat your condition. Only doctors are legally allowed to diagnose. If you are currently working with a health care provider to resolve your injury, this article is not intended to replace or modify your current treatment plan without first consulting your health care professional.

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to diagnose or treat an injury. If you have shoulder pain and are attempting to manage it on your own, stop and work with a professional who is licensed to diagnose and treat your condition. Only doctors are legally allowed to diagnose. If you are currently working with a health care provider to resolve your injury, this article is not intended to replace or modify your current treatment plan without first consulting your health care professional.

Dr. Dan Michael is a chiropractic physician at NW Sports Rehab, a sports rehabilitation clinic in Seattle, WA. He is a former competitive swimmer from Purdue University in W. Lafayette, IN, current medical director of the USTA Washington State Open, and takes special interest in shoulder injury, biomechanics, and performance.

About Destro Machines

Destro Machines is a family and swimmer owned company. We were founded in 2015 when we realized that swimmers and coaches were lacking the effective and affordable training technology required for them to reach their goals. Our team of engineers, has spent months working with Division I College and top tier highschool programs to develop a tower that’s not only less expensive, but also more effective than any other resistance training system available.

Swim training courtesy of Destro Machines, a SwimSwam partner.