Courtesy: Doug Cornish, the founder of Swimpler. Follow Swimpler on Substack here.

This is Volume 2 of “The Imperative – Improved Technique Development”

You can view volume 1 HERE.

Circa 2004, Exercise Physiology class at UNCG

“Doug. Put your hand down. You’re not allowed to ask questions in my class anymore.”

I was a yardage guy. We would log 9-10K SCM in the morning and come back for more in the evening when doubling over the summer. I believed the path toward progress meant doing more.

If I did more practices, swam more yards than my competitors, I would be more prepared. To be fair, it felt like the entirety of swimming in the United States agreed.

Dr. Laurie Wideman had enough. I had been challenging her lessons on matching frequency, intensity, and duration of training to the activity the training was meant to support. When I took the course, I thought that I was finally going to learn science that would help me figure out that magical concoction of laps and training that would unlock a swimmer’s potential. I was left wondering when we were going to talk aboxfrut “more.”

She was fair, though, offering to meet with me for ten minutes after classes as long as I didn’t interrupt. I was embarrassed, but I accepted.

This is how I recall the conversation going after class that day:

“Doug. I’m going to be blunt. Swimmers and coaches…everyone in your world is a joke in mine. You are the only people on the planet who think it makes sense to take an athlete like Usain Bolt and make him run marathons to get ready for a 10-second race.”

I stammered.

She continued.

“First, never show up to class without reading the material again. Second, commit to learning about muscle type, muscle cell structure, energy systems, energy delivery, and how energy systems interact with the endocrine system. Then, you’re going to look into other performance-related areas of science. Dr. Goldfarb is a leader in motor learning. I suggest you introduce yourself and register for a motor learning course next semester. The window for instilling skills is very narrow.”

That conversation shattered my old assumptions and opened my eyes to the science behind training, performance, and how skills are learned and maintained — a science that applies directly to every practice and every swimmer we coach.

I’ve been learning ever since. I think we have it backwards when it comes to swimmer development in the United States.

SKILL AUTOMATION

Have you ever driven for a few minutes while daydreaming but still got where you were going safely?

Have you ever gone for a jog and got lost in your thoughts for 30 minutes without paying attention to your stride?

Swimmers complete practices all the time without ever thinking about their mechanics. Instead they are thinking about the shoes they are going to wear tomorrow, the new song they want to upload to their playlist, the homework they forgot to do, or the lines they fumbled when talking to their crush.

Fitts and Posner offer a three-stage model that explains how a skill goes from unlearned to so well-learned that you can perform it without thinking about it.

Cognitive – Associative – Autonomous

In the cognitive stage, the learner is figuring out what to do. Movements are slow, mistakes are frequent. Imagine getting into your car after work. Instead of a steering wheel, there is a record player. You spin the record clockwise to go right and counterclockwise to go left. Instead of a gas pedal, there is a throttle, like on a boat. Instead of a brake, there is a trigger, like on a bike.

Good luck getting out of the parking lot. Your driving skills are in the cognitive stage.

In the associative stage, the learner knows what to do. Mistakes are less frequent, though still common. Mistakes and focus have a negative correlation. When focus wanes, mistakes increase. Self-correction becomes more prevalent, and movements begin to become more efficient.

You might get out of the parking lot, but in the associative stage, you are not yet ready to merge into traffic.

In the autonomous stage, the skill can be performed while the mind attends to another task. Movements are highly efficient, requiring minimal conscious effort. Swimmers “feel” when something is off.

Congratulations. Your skill has reached the autonomous stage. You can now drive again in any setting or situation while worrying about the bills you didn’t pay or the laundry that you forgot to switch.

There is no definitive number of repetitions that are necessary for a skill to go from unlearned to automatic. Daniel Coyle tackles the acquisition of skill directly in The Talent Code, focusing on the role of myelination. Research is all over the place due to the fact that factors such as practice design, skill complexity, concentration, and levels of persistence are all contributing and variable. In martial arts, you may hear a rule-of-thumb that a punch is mastered in 10,000 repetitions. Other fields suggest that 10,000-50,000 repetitions are needed for a skill to become “reflexive.”

Let’s pretend that 50K is the secret number of repetitions that will take a skill from unlearned to automatic or reflexive, and compare to a made-up scenario of a swimmer between the ages of 8 and 10.

At age 8, they came to practice 2 times per week, logged 1,500 yards each time, and took 26 strokes per lap.

- 156,000 repetitions/year

At age 9, they came to practice 3 times per week, swam 2,500 yards per practice, and improved to 24 strokes per lap.

- 360,000 repetitions/year

At age 10, they came to practice 4 times per week, swam 3,000 yards per practice, and improved to 22 strokes per lap.

- 528,000 repetitions/year

On the surface, this swimmer has logged almost 900,000 repetitions. When you add the repetitions from warm-ups, races, and summer league, their skills have been reinforced well beyond 1,000,000 times.

Now, realize that the repetition abacus tallied the first strokes shortly after their lesson instructor exuberantly performed, “Great job – now let’s add big arms!”

SKILL RE-AUTOMATION

Have you ever heard a coach say, “the swimmers just don’t listen – I’ve been telling them that for months?”

While it is true that the attentionality of the swimmer is critical in skill development, coaches would do themselves and their swimmers a favor by understanding the three reasons it is so difficult for an athlete to replace an automated skill with a new skill.

Myelination

Learned skills have neural circuits that have been myelinated. Myelin insulates the nerve pathway, providing faster transmission from nervous system to muscle. The electrical impulse will travel down the path of least resistance and most efficient pathway.

Interference

When you are attempting to replace a skill with a new skill, the old code doesn’t disappear. It interferes. Essentially, it’s like trying to run the old version of Windows while the new one is uploading – impossible. There is a reason that your system must shut down.

Conscious Control

While the nervous system prefers the myelinated pathway and the old system interferes, you have one additional obstacle, the attention of the swimmer.

Remember, this swimmer has learned to execute the skill without thinking about it. If it takes 50K repetitions to automate an unlearned skill, how many more repetitions will it take to replace it?

Furthermore, on how many of those reps can the athlete exert 100% conscious control while fighting the nervous system, the interference, and the fatigue and repetition combination required to complete the practice?

Let’s revisit that imaginary, but all-too-common, scenario from above.

You are the lead 11-12 group coach. The swimmer is now 11 and is under your tutelage. It is obvious to you that the best way for you to help the group is to enhance skills. The head coach has even remarked that their technique is substandard.

You must undertake this re-automation challenge while countering an emotional one — the swimmer may feel frustrated or resistant when asked to change something that feels automatic, and the coach must navigate the motivational hurdles of helping athletes unlearn deeply embedded patterns.

Understanding the underlying science of motor learning is important.

But understanding the role of repetitions in skill automation is only part of the story. We also need to understand how those skills stack and interact — and how poor layering can quietly sabotage progress.

SKILL LAYERING

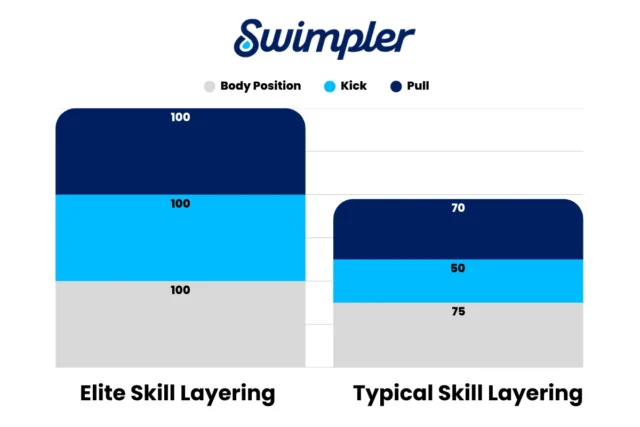

Coaches, lesson instructors, swimmers — consider this image and the caption:

The body is the vessel – body position. The arms are the oars – strokes. The legs are the motor – kicks.

The goal is to execute body position, kick, and strokes simultaneously at 100% proficiency.

The most foundational of the three skills is fairing — the process of smoothing the lines of a boat to reduce drag. It’s the first, most foundational, and most critical skill in the sport.

If the boat doesn’t float, the motor doesn’t matter.

Body position is your foundation.

Once you have a hydrodynamic, balanced boat, adding a motor (layering) is pretty simple. It’s relatively easy for a swimmer to maintain 100% integrity of the body position when adding a kick — especially when using a snorkel.

What happens, though, when we add the oars?

The moment a swimmer has layered the kick onto the body position and can execute both at 100% integrity, we add the arms and start building the yardage base. In my opinion, this is the biggest performance-limiting moment in the entire sport.

Because we don’t spend enough time automating the foundational skills of body position and kick, there is massive skill degradation when we add arms. Skills that independently can be executed at 100% proficiency degrade when combined, seriously inhibiting the swimmer’s ability to move through the water relative to someone who layered their skills more patiently and with more integrity.

When we ignore this, we don’t just stall progress — we lock swimmers into inefficiency that can take years to unwind, if it can be unwound at all. Every lap layered on top of poor fundamentals compounds the problem, wasting precious time in an athlete’s narrow developmental window.

Have you ever wondered how elite swimmers make it look so easy?

They aren’t doing anything superhuman. They are layering basic skills in a way that each one holds integrity under pressure, under speed, under fatigue, and when done simultaneously. Where others break down, they hold form. The difference isn’t magical talent; it’s layered mastery.

An example of how potential is lost by not layering skills at 100% is shown in the graphic below.

Elite Skill Layering: layering body position, kick, and strokes, performing them simultaneously without degradation.

Typical Skill Layering: layering body position, kick, and strokes, performing them simultaneously with degradation.

TAKEAWAY

If we want to elevate swimmer development in the U.S., we must rethink how we layer skills. Fair the vessel first — smooth the body lines and reduce drag. Then add the motor — build a clean, effective kick. Only after these are mastered should we add the oars — refining the pull and catch. We should be reconsidering the developmental models under which our athletes progress. From lessons to elite. We should be including training plans that give athletes time to solidify foundational skills, create checkpoints before layering complexity, and prioritize quality over quantity enough to ensure that the swimmer is still progressing toward full potential.

Rushing this process doesn’t just limit performance; it engrains inefficiency. Patience, precision, and intentional progression aren’t just good coaching — they’re the foundation of long-term success.

UP NEXT:

- The Efficiency Model

- Base Position of Teaching Technique

- Conceptual Definition of Full Potential

Thank you for these articles. There is a ton of food for thought in them. My experience accords perfectly with the statement near the end: “Rushing this process…engrains inefficiency.”

Excellent article and I agree 100%. It is very hard to keep repeating the same story to a beginner or new learner but the Coach must find a way to keep the learner interested and motivated to keep trying and that is the hard part especially with young students.