Courtesy: Tom Slear

On the day last month when Dan Butler died, his wife, Kitty, woke up early, as she often did, and left their bedroom to read. When she returned, Dan was still showing the lingering effects of the flu that he had endured to one degree or another since January. His cough was loud and worrisome, but more disturbing was his breathing, which Kitty described as “weird.”

“You are worrying me, Boyfriend,” she said, but Dan being Dan waved her off. The three-time Paralympic swimming gold medalist had been paralyzed from the waist down nearly 43 of his 65 years. He had some very, very dark days early on, particularly during the six months he was in a body cast, but once liberated to a wheelchair he began, as he wrote in an email years later, “To reconfigure my sense of who I am and how I fit into society, almost like a second adolescence.” The salient characteristic of this new construct was an absolute refusal under any but the most dire circumstances to ask for help.

“He never did with me, not once,” says Billy Demby, a long-time friend who lost both legs in Vietnam after a rocket propelled grenade hit a truck he was driving. “One time he was giving me a ride and like most paras (paraplegics), he would get in his car on the passenger’s side and slide over (to the driver’s seat) and then put his wheelchair in the car. When I offered to help with the wheelchair, he said, ‘No, no, no. I got it.’”

Demby chuckles a bit when telling the story. He is a double-amputee. Those of you of a certain age might remember the prosthetic commercials he did for DuPont. He can walk. His help would have made the task easier and faster. But convenience made no impression on Dan.

“It was like an insult to him,” Demby says. “Most paras I’ve met in my time have that kind of determination, but Dan’s was overwhelming.”

“I got bit by that dog too many times,” says Dan’s younger brother Bill. “Try to help him and he would get mad. The guy never complained about anything. He just sucked it up.”

Kitty had been bitten by that dog as well and knew better than to argue. She met Dan in 1982 on a beach near Annapolis, Maryland. She claims she hardly noticed the wheelchair. In the intervening 38 years she had seen him do everything but climb stairs. She and their two sons, Jeff, 35, and Sam, 26, had chucked sympathy long ago, convinced he didn’t need it and knowing he didn’t want it.

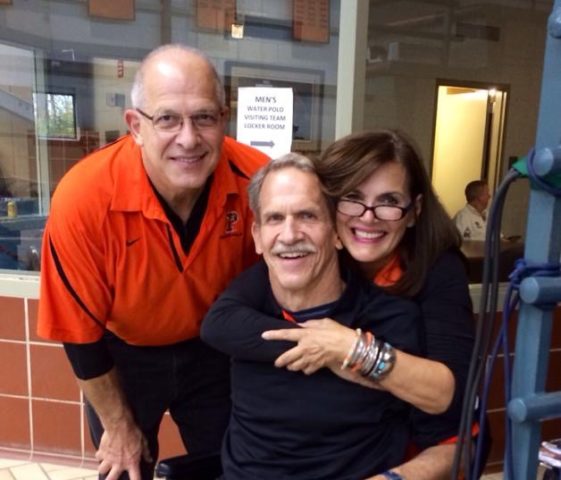

Dan and wife Kitty with Dan’s brother, Bill, at Princeton University for a water polo game. Dan and Kitty’s younger son, Sam, played water polo for Princeton from 2010 through 2014.

Kitty was reassured somewhat the day before when he arrived home excited, telling her he had a great day at work. That was Dan, she thought, always in the moment, always positive. The coughing and labored breathing, he insisted the next morning, was just a process for “breaking things up.” She left to take a shower.

When she returned a half hour later, her husband was dead. The cause was recorded as cardiopulmonary arrest. Despite her grief, she spent much of the day calling family members, and one person who was almost family.

“I would not let the sun set that day without calling Don May,” she says. “Dan was so much of who he was because of Don May.”

May was the head swimming coach at Guilford High School in Rockford, Illinois, for four decades. Dan was the team captain his junior and senior years in 1972 and 1973. Dan’s best times, which May has at his fingertips because he recorded them meticulously as he did the times of all of his other swimmers, indicated potential for Division II and III, if not lower Division I. But Dan wasn’t interested. He wanted an active life outdoors and away from the pool. He went on to earn a degree in Zoology at the University of Washington. But a short time after graduation while visiting one of his older sisters in DeKalb, a town 45 miles southeast of Rockford, he rode a bike to get ice cream and blew through a stop sign. A car sent him 20 to 25 feet in the air. He fell through the windshield and broke his back.

May started visiting when Dan was in the hospital. May downplays his influence on Dan, recalling that he showed up at the Guilford High School pool unexpectedly. Not so, says Bill Butler, who also swam for May. He remembers with conviction the short conversation that started Dan on his post-accident swimming career:

May: Let’s go.

Dan: Go where?

May: The pool. You can’t keep sitting around.

May rigged a pull buoy with a wide rubber band to put around Dan’s ankles and keep his legs up.

“He got in and started swimming right away,” says May from his retirement home in New Mexico, “and he was pretty darn good.”

Dan swam nearly every day for an hour or more from then until just over a year ago when he injured his shoulder climbing out of a pool. He allowed nothing to interfere with his daily swim — not trials when he was an assistant U. S Attorney, not business trips or vacations (he would undertake extensive due diligence to find a hotel with pool big enough to do laps) and not family dinners. Kitty can’t remember a weekday night when he was home for an evening meal. He worked until six each evening and then swam at a pool near their home in northern Virginia. He typically ate after 9:00 pm watching television with Kitty and, as they grew older, his sons.

“He got addicted,” Bill says. “It was a way for him every day to get his exercise, clear his mind and help his mood. ”

“It was his oxygen,” says Kitty.

It also was his competitive outlet. Dan won his first national championship in 1980. He went on to make three U. S. Paralympic teams, mostly as a butterflier. He won a bronze medal as a member of a 200-meter medley relay in 1992. Four years later in Atlanta he won a gold medal in the 50-meter butterfly and two gold medals in the 200-meter medley and freestyle relays. In 2000 in Sydney, he was sixth in the 50-meter butterfly and a member of the 200-meter freestyle relay that finished fifth. (The medley relay he was on was disqualified in the preliminaries.)

Eleven months after the accident Dan started law school at California Western in San Diego. While registering for classes, he met Dan Mazzella, a classmate who needed a place to stay. Dan Butler had an extra bedroom in his apartment. Mazzella watched his roommate grow up as a paraplegic. He did wheelies to mount a sidewalk if it didn’t have a cut from the street, or to descend one- or two-step stairwells. He rode up and down escalators backwards on the large wheels with his hands gripping the rails. When Mazzella told a law professor that Dan had been in a wheelchair for just a year, the professor was so startled that he went to his knees. He had assumed Dan was born paralyzed. He couldn’t fathom an adult progressing so quickly from paralysis to no limits.

Dan worked as an intern at the U. S. Attorney’s Office in San Diego over his last 18 months of law school and took to it as much as he did to swimming following the accident.

“It is that sense of spending your professional time, effort and energy in something greater than oneself, public service at its best,” he said during a speech he gave in 2008 after receiving an award from the National Association of Assistant U. S. Attorneys. “To have no greater goal than to strive to what is right as best as you can discern it, that is a great job to have.”

After graduation, he joined the Department of Justice and stayed until the end. He started in the Civil Rights Division and moved to the Public Integrity Section of the Criminal Division in 1989 and, in 1999, the U. S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia. It was there that he took on two cases that brought his name into the national news. The first was in 2008 when he prosecuted the case against Deborah Jeane Palfrey for money laundering and racketeering. Palfrey ran an upscale escort service. The press dubbed her the D. C. Madam and tried relentlessly to get a full accounting of her clients only to come up emptyhanded. The names uncovered weren’t particularly rich or powerful. But Dan won, though Palfrey killed herself before sentencing, thereby unleashing a cornucopia of conspiracy theories.

Dan in 2011 on his way to a courthouse with two other Department of Justice lawyers and an FBI agent.

The other was the perjury case against Roger Clemens, the only retired pitcher with more than 300 wins who is not in the Hall of Fame. The case was referred to the Justice Department by Congress after inconsistencies in Clemens’s testimony relating to performance enhancing drugs. Any lawyer will tell you that perjury is one of the most difficult cases to make. Add on the burden of going after a celebrity and you are left to wonder why Dan took it on.

“He could have easily cut and run,” says Steve Durham, who prosecuted the case along with Dan. “But Dan stood for accountability. Win or lose, it didn’t matter. He wanted people held accountable.”

However, Clemens wasn’t. A mistrial in 2011 was followed by an acquittal in 2012. Still, Dan won many more cases than he lost while establishing an immutable reputation for integrity in all matters big and small. Kitty once took a liking to a commemorative pen and asked Dan if she could take an extra one home.

“Of course not,” he said. “That would be stealing.”

Kitty rolled her eyes. Oh, Dan, please. She later went through his briefcase and sent back all of the government pens she found.

“He always told me not to let the perfect get in the way of the good,” she says. “I guess that’s why he never complained about my cooking.”

I just learned of Dan’s death. What a loss! My sincere condolences to Kitty and the boys. Hope you are all well and happy.

This is such an endearing story of a truly remarkable person. Dan made the world a better place.

A class act. I had the privilege of working a couple summer league swim meets with Dan (he was ref, while I did S&T). The wheelchair might as well have been a hat or a clipboard: after a few minutes, you simply didn’t notice. Just another dad, working his kid’s swim meet. I’m fortunate to have met him.

Beautiful story. No other words.

We need more Dan Butlers in our lives today, he epitomized the words ” public servant”. The world was a better place with Dan in it. May his family find comfort in Mr. Slear’s wonderful words.

What an amazing story. Rest in peace Dan.