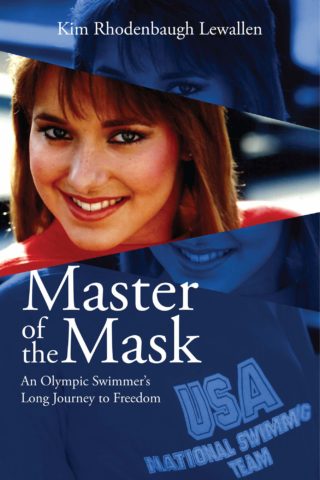

1984 Olympian, Kim Rhodenbaugh Lewallen, digs deep her memoir MASTER OF THE MASK, a raw account of her struggle with addition and suicide attempts, all the result of horrific sexual assaults. Kim’s journey is triumphant, leading to freedom after decades of pain, and she offers hope and valuable resources as a measure of prevention.

Book Excerpt

It was the Opening Ceremonies for the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. Since we were the host country, the United States was the last team to march out. The crowd was pumped! As we entered the tunnel of the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, we could hear them chanting, “USA, USA.” As we got closer to the opening, the cheering got louder and louder. When we entered the coliseum, the crowd went wild as they continued to chant, “USA, USA, USA” over and over while waving American flags.

I will never forget that moment of hearing 90,000 screaming fans there to support us. The feeling of pride for my country and all of my accomplishments felt overwhelming. I’m so glad I could bask in that moment. I had made it! I’d fulfilled my lifelong dream to make the Olympic Swim Team, a dream I had from the age of ten. But that would be the only happy memory I would have from the Olympics. On the outside, I looked like a happy and confident person, but inside I was dying. I had a dark secret that I’d been living with, and it was killing me.

I grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, in a powerhouse, competitive swimming family. I was the seventh of eight children. My mom’s license plate read “8FISH” and my dad’s, “SWIMIN”; put them together and you get, “8FISH SWIMIN.” It was a family sport. We loved, encouraged, and motivated each other.

As an adult, I found out I had ADD and a vision impairment called Vertical Phoria, which explained why I had such a difficult time in school. Swimming became my salvation; I could dive into the water and drown out all the sounds that drove me crazy. It was something I excelled at and in which I built my confidence.

I loved everything about swimming − the feel of the water, the practice of setting goals and the joy of achieving them, the competitiveness, and the incredible friendships. I was very coachable, extremely hard-working, and intensely determined. By the age of eight years old, I’d won events at the state level; at age eleven I made my first Junior Nationals, and at thirteen I competed in my first National Championship. Life felt beautiful then, full of joy, success and certainty. Little did I know that all of that would quickly be stripped away.

The sport of swimming is filled with remarkable people, and I was blessed with many phenomenal coaches and teammates, but there are always some bad apples in the bunch. Over the years I’ve read many articles about coaches abusing their athletes, but at the time of writing this book, I’ve found very few articles about athletes who’ve sexually assaulted other athletes. This is what happened to me. My intent is not to divulge names but to expose the ugly truth that sexual abuse against other athletes happens and is probably more prevalent than we all realize.

In 1980, I had just made my first U.S. team at the age of fourteen. My dream of one day making the Olympic Team was on course, and I was thrilled to represent my country. We were swimming at an international meet in Honolulu and were staying in the dorms at the University of Hawaii. One day while taking a nap in my dorm room, I suddenly woke up to someone fondling me. To my horror, it was one of the older male swimmers from the U.S. team whom I barely knew. I remember shoving his hand away from me. With a sick smile on his face, he left my room not saying a word. I felt very confused, fearful and ashamed. My self-defense mechanisms kicked in, detaching me from what took place, but the damage had been done.

I became a master at putting on a “happy mask,” but inside I remained fearful and distrusting. My once confident self became fixated on all my insecurities and obsessed over my weaknesses. Despair replaced my joy. This predator proved to be the first of three swimmers who eventually sexually assaulted me. I’ve told people I felt like I had an antenna on my head so the abusers could find me, as if they had a sick sense of the ones who have already been abused or who they could control and manipulate.

The top of my swimming career peaked in 1982 at age sixteen. I’d made the World Games Team and earned two silver medals in the 100 breaststroke and the 4 x 100 medley relay. After the meet, I joined a few swimmers for a party in one of the hotel rooms to celebrate. The others drifted off as the evening went on, and I realized it was just one of the male swimmers and me. I had a crush on him, and so I didn’t mind him kissing me, but he wanted more. I was a virgin at this point and didn’t feel ready to have sex. When I saw things going in that direction, I told him to stop. He didn’t and he raped me. I remember him overpowering me ̶ I told him no, but he didn’t stop. Paralyzed with fear, I felt like I was drowning with no rescue in sight.

Although I drank alcohol from time to time, after being raped my drinking became excessive, and I started smoking pot to numb the pain. I just wanted to forget the horrific memory. Although this same swimmer owned up to what he had done and apologized to me a year later, it was too late. The seeds of self-loathing, shame, and fear became further deeply rooted. I had thoughts of suicide, many times wanting to run my car off the road. Like the first assault, I told no one.

My parents, who have always been so amazingly supportive, have since asked me why I never told them back then. I didn’t really have an answer, other than I simply couldn’t. The shame of it all had me believing the lie that I deserved the blame for the abuse. My mind deceived me into thinking that keeping my secrets protected me when, in reality, not telling anyone kept me in darkness. This unbearable heaviness stayed with me for more than thirty years.

The third swimmer who sexually assaulted me caused the most damage. It was my senior year in high school and Olympic year in 1984 − a year that should have been one of the happiest years of my life. At the beginning of that year, our Cincinnati Marlins team traveled on a bus to a swim meet. I was sitting next to one of the older male swimmers who had been like a brother to me. At some point, I dozed off. I woke up to this same brother figure with his hands down my shorts. Panicked, I shoved his hand away and sat paralyzed with shock. I’d known and trusted him since I was a little girl! Gripped with deep anguish, I could no longer be silent. I told one girlfriend, something I had never done. She betrayed my trust by telling my abuser’s girlfriend and my boyfriend about the incident, making it look like I had instigated everything. I learned to never tell anyone about my abuse ever again.

Soon after, I developed an eating disorder. I felt so out of control that I thought, Here’s something I can control. This compounded shame caused me to very quickly spiral totally out of control. On top of all the emotional trauma, I was afflicted with intense hunger pains, horrible intestinal discomfort, dehydration, fatigue, and headaches. Most days we trained up to six hours, and I managed that with hardly any nourishment. I would either binge and throw up, or I wouldn’t eat. This began a ten-year battle with bulimia and anorexia. I drank or smoked pot to escape the “hell” I endured. I put everything I had into every practice but never felt like I’d done enough, so I would come home only to do more sit-ups and push-ups. Every day I had to see this same brother figure who had sexually assaulted me.

I don’t know how I made the Olympic Team other than by God’s grace. By the time I got to the Olympic trials, my body started shutting down. I should’ve won an Oscar for my acting! I pretended like everything was okay, when in reality, I was anything but okay. On the outside, I looked confident, happy and capable, but inside I felt broken, fearful, and deeply depressed. Agonizing physical and emotional pain made me very weak. By nothing short of a miracle, I ended up making the team in the 200 breaststroke, which is a grueling event.

The opening ceremonies were a great memory, but the rest of my Olympic experience continued to be horrible. Two of the three who had assaulted me were also on the team. The stress of seeing my abusers on a daily basis proved to be unbearable. I stayed consumed with crazy thoughts and felt like I was going insane. Yet another miracle happened. I made the finals! My best time would have medaled, but the night of the finals, I didn’t even think I was going to be able to finish the race. Every muscle locked up on me. With excruciating pain, I persisted slowly like swimming through mud. My Olympic experience ended with an eighth-place finish and feelings of disappointment and unworthiness. All I wanted to do was forget what happened to me and move on, but I couldn’t move past the memories of abuse. So, I continued to put on a “smiley face” and go on like nothing had ever happened. This decision led to many years of alcohol and drug abuse, shame, depression, and suicide attempts.

Master of the Mask can be purchased at Nation of Women Publishing here.